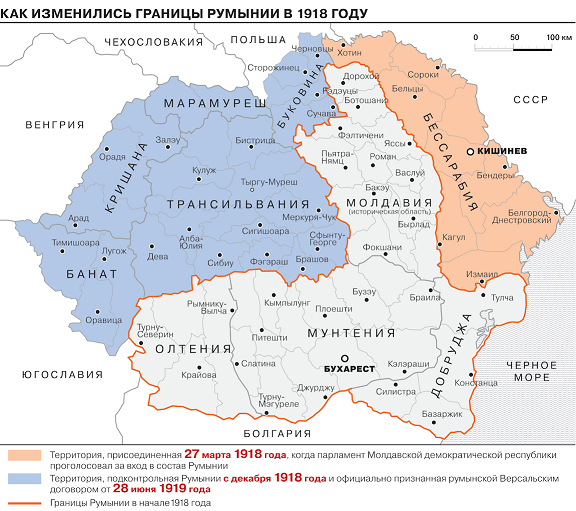

This year has become special for Romania. The country has marked the 100th anniversary of the Great Unification. It is about 1918, as a result of the First World War, after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires, the Transylvania joined the Romanian kingdom, and Bessarabia and Northern Bukovyna did it even earlier. Then the country was called “Great Romania” and it claimed the role of regional leader.

The unification of 1918 is considered the most important event in Romanian history, and in 1990, December 1 was approved as a national holiday. But since this date is historically linked only with the entry of Transylvania into the Romanian state, last year the Romanian MP from the National Movement Party (NMP), one of the companions of Romania’s ex-president Traian Basescu Eugen Tomac offered another national holiday – March 27 (Day of “reunification” of Romania and Bessarabia).

NMP took full advantage of this legislative initiative in 2018. Since the beginning of this year, unprecedented events have been held in Moldova with its support.

March 25, a many-thousand rally of supporters of the union with Romania was held in the capital of Moldova. The Moldovan authorities counted about 7 thousand participants. The organizers assured that more than 100 thousand people gathered at the central square of Chisinau.

The event was organized by the Moldovan Unionists, led by the National Unity Party (NUP). And headed by Gheorghe Simion, leader of the Moldovan platform of unionists Acţiunea 2012, Dorin Chirtoaca, former mayor of the Moldovan capital, first vice-chairman of the Liberal Party of Moldova, and Traian Basescu, ex-president of Romania, honorary chairman of the NUP.

On March 27, a formal solemn meeting was held in the Romanian parliament, but with the participation of Moldovan parliament and government representatives, led by Speaker of the Moldovan Parliament Andrian Candu.

The general picture on the eve of the holiday was supplemented by Basescu’s intention, announced earlier this year, to submit to the Romanian parliament a declaration on Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact denunciation with a view to reconsidering the transfer of a number of territories in Eastern Europe to the USSR.

Neither the idea of the Romanian ex-president about the denunciation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, nor the mass rallies of the Unionists with the slogans of “reunification” of Romania are not something new.

In 2009, the State Duma of the Russian Federation condemned the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and at a ceremony in Gdansk (Poland), Putin called on other countries that “went on a deal with the Nazis” to do the same. However, in 2015 the Russian president revised his views and actually justified the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, supporting the opinion of Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky that the pact was necessary to ensure the security of the Soviet Union.

Another striking example is that in September 2016, Polish Sejm adopted a resolution condemning the pact, but in October of the same year signed the Declaration of Memory and Solidarity together with the Ukrainian parliament.

In August 2010, Moldova took an attempt to adopt a document condemning the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact at the state level. Then, Liberal Party of Moldova led by Mihai Ghimpu was at the peak of popularity in the republic; its program activities were also based on the ideas of unionism. The party was then part of the ruling coalition “Alliance for European Integration.” And Moldovan Prime Minister Vlad Filat (2009-2013), who was not a unionist, shared the idea that Moldova was “the second Romanian state” and that the state language of the country should be called only Romanian. Even after the collapse of the coalition in 2013, the liberal party has been gaining up to 20% of the support for another two years, and in the local elections of June 2015, it showed the fourth result (12.6%). But after the election of the country’s president, socialist Igor Dodon, the ratings of the liberals did not exceed 2%.

Each of these countries invested in their decisions their own interpretation of those historical events. But none of them, unlike Basescu’s proposed document, openly indicated the possibility of revising the borders of the existing states.

In addition, this year there was an event that goes beyond the previous public statements of the Unionists. A the end of January, Civil Platform Acţiunea 2012, which includes non-governmental organizations from Moldova and Romania, supporting the unification of both countries, initiated “100 villages – 100th anniversary of the unification” campaign, carried out to sign the declaration by the populated areas of the republic for unification with Romania. The symbolic document was approved by the authorities of almost 14.5% of villages and towns of the Republic (organizers collected signatures of more than 130 villages, cities, and even districts of Moldova – 898 settlements). March 10, more than hundreds of mayors and members of rural councils of Moldovan settlements took part in a conference in Romanian Iasi. Together with representatives of the local authorities of Romania, they adopted a resolution on the unification of the two countries.

In addition, this year there was an event that goes beyond the previous public statements of the Unionists. A the end of January, Civil Platform Acţiunea 2012, which includes non-governmental organizations from Moldova and Romania, supporting the unification of both countries, initiated “100 villages – 100th anniversary of the unification” campaign, carried out to sign the declaration by the populated areas of the republic for unification with Romania. The symbolic document was approved by the authorities of almost 14.5% of villages and towns of the Republic (organizers collected signatures of more than 130 villages, cities, and even districts of Moldova – 898 settlements). March 10, more than hundreds of mayors and members of rural councils of Moldovan settlements took part in a conference in Romanian Iasi. Together with representatives of the local authorities of Romania, they adopted a resolution on the unification of the two countries.

This event should be considered as a precedent that can be later used by Bucharest as a legal and ideological justification for territorial claims to Moldova.

Should Ukraine be afraid of this?

Is it possible that such tactics would be used against our country in places of compact residence of ethnic Romanians? These days, neither Chisinau nor the Romanian Parliament voice opens statement concerning the south of Bessarabia or the north of Bukovyna (part of Ukraine’s Odesa and Chernivtsi regions). Moreover, Basescu made it clear that his activities in Moldova do not affect the interests of Ukraine.

He said that it was only about restoring the border of Romania along the Dniester. Ukrainian question was openly raised by the Unionists two years ago. Then “Sfatul Țării-2” Congress, established in Chisinau, proposed to give Ukraine Transnistria in exchange for the south of Bessarabia and part of Bukovyna. Civil Platform Acţiunea 2012 became the organizer of the congress. But even with the current optimistic forecast of Kyiv, one should not forget that Romania and Moldova has a large number of supporters of territorial claims to Ukraine.

For example, in an interview with Ogonek magazine, one of the most famous historians of Romania, Professor Ioan Scurtu recently stated that he “always said that this democratic Ukraine, which wants to join NATO, has profited most from the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.” It becomes obvious from his words that Bucharest has ceased to take any steps towards territorial claims to Ukraine since 2014. This was due to the change of power in Romania itself, the Eurointegration and Euro-Atlantic self-determination of Ukraine and, of course, Russia’s occupation of Crimea, Donbas conflict, and the reaction of the West.

Bucharest still continues to hold the same views concerning Ukrainian question. Let us remember its reaction (together with Hungary) to Ukraine’s law “On Education”. Then, at a meeting of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, where the law was discussed, People’s Deputy of Ukraine Iryna Gerashchenko noted that “aggressive statements of some representatives of the Hungarian and Romanian delegations can be considered as hidden territorial claims to Ukraine, and this is unacceptable.”

Elections first

At the end of November, Moldova to hold the parliamentary elections, using a new mixed system. The Democratic Party under the leadership of the oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc will try to stay in power. The main rival of NMP would be president’s party of socialists. The National Unity Party, which promotes the idea of uniting Moldova with Romania, is a young political force with rather modest ratings – 0.5-0.7% (according to the latest sociological surveys of February 2018 conducted by the “Barometer of Public Opinion”, with the funding of the Soros Foundation).

According to experts, the NUP has all chances to get into the Moldovan parliament this year and join the coalition with the ruling democratic party.

NUP has the support of the Romanian opposition NMP, which is represented in the European Parliament, is a full member of the European People’s Party and has 8 seats in the Senate and 17 seats in the Chamber of Deputies of Romania. Honorary chairman Traian Basescu also gives authority to NUP in the eyes of Moldovans.

The latest sociological surveys conducted in November 2017 by the Public Opinion Foundation show that 62.8% of respondents in a possible referendum would have voted against the accession of Moldova to Romania. However, 23% of those polled would immediately say yes. At the same time, 8% of citizens did not decide on the answer, and 5.9% said they would not participate.

The popularity of unionism in Moldova is constantly growing, the senior researcher of the Center for Post-Soviet Studies at the Institute of Economics of the Russian Academy of Sciences Andrei Devyatkov assures. Firstly, a change of generations takes place in Moldova, and a significant part of modern Moldovan youth falls under the Romanian cultural and educational influence. Secondly, the so-called pragmatic unionism, when many people, regardless of social status, mass poverty, an outflow of population, corruption of politicians, constant political instability, are disappointed in Moldova as a state. Basescu uses this situation, arguing that the only way to the EU is for Moldova is through unification with Romania.

In turn, Moldovan politician and journalist, former chairman of the Christian Democratic People’s Party Iurie Rosca believe that if the unification of Moldova with Romania becomes possible, it will be implemented in two possible scenarios. The first one is the military, following the Georgian and Ukrainian models, including military actions, the loss of Transdniestria in favor of Russia (or Ukraine in the event of Russia’s weakening), the entry of NATO and Romanian troops into the territory of Moldova “to maintain peace,” and then (or simultaneously) a merger with Romania. The second, more gentle and peaceful, with an observance of legal formalities.

Therefore, most likely, the current movement of the Unionists is based on a short-term perspective. They want to take revenge on the parliamentary elections scheduled for November 2018 in Moldova. And statements about the “reunification” of great Romania is a long-running issue (and nothing more than a pre-election PR move).

According to Vladislav Kulminsky, executive director of the Chisinau Institute for Strategic Initiatives, the theme of unionism is profitable for both the pro-Western government of Moldova and the pro-Russian president Igor Dodon. “Without the encouragement of the authorities, it would be impossible to adopt declarations on unification with Romania,” Kulminsky said. “The activation of the Unionists gives the authorities the opportunity to create their own agenda. They take a step for geopolitics. This is also a wonderful gift to the Socialists, who during the election campaign would speak about the danger of unionism and thereby distract the voter from the real problems,” he added.

With all this, we should not forget that speculation with the historical past is very fraught with grave consequences for the relations of the neighboring countries. During the times of Putin’s Russia, they began to warm up the cult of the “primordially Russian Crimea,” which resulted in the annexation of the peninsula in 2014. By the way, many experts are sure that this has been done to raise Putin’s ratings. In Poland, right-wing forces came to power and also raised questions of the historical past. This has already resulted in the deterioration of relations between Warsaw and Kyiv.

In addition, Polish nationalists are increasingly speaking about the “Polish Lemberg”, referring to the past of Lviv. The observers point out that the aggressive foreign policy of Polish PiS could be explained with the struggle for the votes. In Hungary, PM’s Viktor Orban’s party, which is losing its ratings, has suddenly “remembered” the problems of the Hungarians of Transcarpathia. Ukraine is concerned about Hungarian territorial claims on the region. This has aggravated relations between countries. These lessons indicate that the threat of turning pre-election themes into real territorial disputes is quite possible and dangerous.

3 Comments

I reckon that Ukraine should give up lost Romanian territory including the Snake Island. Ukraine acquired Romanian lands from USSR, and the Soviets got it by force from Romania.

The Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina took place from June 28 to July 4, 1940, as a result of an ultimatum by the Soviet Union to Romania on June 26, 1940 that threatened the use of force. Bessarabia had been part of the Kingdom of Romania since the time of the Russian Civil War and Bukovina since the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, and Hertsa was a district of the Romanian Old Kingdom. Those regions, with a total area of 50,762 km2 (19,599 sq mi) and a population of 3,776,309 inhabitants, were incorporated into the Soviet Union.On October 26, 1940, six Romanian islands on the Chilia branch of the Danube, with an area of 23.75 km2 (9.17 sq mi), were also occupied by the Soviet Army.

The Soviet Union had planned to accomplish the annexation with a full-scale invasion, but the Romanian government, responding to the Soviet ultimatum delivered on June 26, agreed to withdraw from the territories to avoid a military conflict. The use of force had been made illegal by the Conventions for the Definition of Aggression in July 1933, but from an international legal standpoint, the new status of the annexed territories was eventually based on a formal agreement through which Romania consented to the retrocession of Bessarabia and cession of Northern Bukovina. As it was not mentioned in the ultimatum, the annexation of the Hertsa region was not consented to by Romania, and the same is true of the subsequent Soviet occupation of the Danube islands. On June 24, Nazi Germany, which had acknowledged the Soviet interest in Bessarabia in a secret protocol to the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, had been made aware prior to the planned ultimatum but did not inform the Romanian authorities and was willing to provide support. On June 22, France, a guarantor of Romanian borders, fell to Nazi advances. This is considered to be an important factor in the Soviets’ decision to issue the ultimatum. The Soviet invasion of Bukovina in 1940 violated the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, since it went beyond the Soviet sphere of influence that had been agreed with the Axis.

On August 2, 1940, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed as a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, encompassing most of Bessarabia and part of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, an autonomous republic of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic on the left bank of the Dniester (now the breakaway Transnistria). The Hertsa region and the regions inhabited by Slavic majorities (Northern Bukovina, Northern and Southern Bessarabia) were included in the Ukrainian SSR. A period of political persecution, including executions, deportations to labour camps and arrests, occurred during the Soviet administration.

In July 1941, Romanian and German troops occupied Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and Hertsa during the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union. A military administration was established, and the region’s Jewish population was executed on the spot or deported to Transnistria, where large numbers were killed. In August 1944, during the Soviet Second Jassy–Kishinev Offensive, the Axis war effort on the Eastern Front collapsed. The coup of 23 August 1944 caused the Romanian army to cease resisting the Soviet advance and to join the fight against Germany. Soviet forces advanced from Bessarabia into Romania, captured much of its standing army as prisoners-of-war and occupied the country. On September 12, 1944, Romania signed the Moscow Armistice with the Allies. The Armistice and the subsequent peace treaty of 1947 confirmed the Soviet-Romanian border as it was on January 1, 1941.

Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and Hertsa remained part of the Soviet Union until it collapsed in 1991, when they became part of the newly independent states of Moldova and Ukraine. The Declaration of Independence of Moldova of August 27, 1991, declared the Soviet occupation illegal.

Incessantly, for 25 years out of 30 years of its modern history, Russia has brought nothing but death. Now we have the chance to stop Russian war-machine forever

Dniester, Russia and Moldova are Slavs