Shades of ‘whiteness’: immigration and the role of British newspapers before the EU referendum.The anti-immigrant drumbeat in the lead-up to the EU referendum was anything other than benign.

Influenta politica a mass mediei Britanice

Immigration has been, and continues to be, a topic of enduring debate in the British media. The lead-up to the 2016 EU Referendum exposed and sharpened already divisive opinions, and media coverage of the referendum became an extended battleground in the war of words over the role and place of migration in British society.

Coverage reached fever pitch in the month leading to the referendum, with some outlets openly using language that racialised immigration and immigrants: language that created and established differences between the British ‘self’ vs the European immigrant ‘other’.

Racialised language in mass media has the potential to shape perceptions of race and the way that we think of ourselves in relation to others. It can determine who is included and who is excluded in society.

It is therefore important to look at how newspapers racialised immigration from the EU in the lead up to Britain’s historic vote to leave the European Union, as this exposes the ways though which immigrants who are ‘white’ in terms of skin colour are nevertheless categorised as being racially different and ripe for exclusion as a result.

What is ‘whiteness’? Rather than biological trait, ‘whiteness’ needs to be understood as a collection of (generally positive) social and cultural features that are imagined and constructed. Whiteness is thus far from absolute – it comes in shades. To be ‘white’ can, to an extent, be understood in terms of class, and includes such factors as wealth, profession, legal standing, language proficiency, and perceived contribution to society as well as physical skin colour.

Prior to the referendum EU immigrants were frequently constructed as less ‘white’ than Britons. As impoverished ‘Others’ lacking certain ‘white’ attributes, they threatened Britain’s quality of life and their inclusion was undesirable. Such arguments were most often made by the right-wing parties and politicians spearheading the Leave movement.

They were then repeated in the pages of newspapers sympathetic to the cause of excluding immigrants from British society through a successful Brexit. Racialisation was not, however, the sole province of the far right or tabloid press in this political context. With some effort it was also possible to find examples of these processes at work in left-leaning and ‘quality press’ as well.

They were then repeated in the pages of newspapers sympathetic to the cause of excluding immigrants from British society through a successful Brexit. Racialisation was not, however, the sole province of the far right or tabloid press in this political context. With some effort it was also possible to find examples of these processes at work in left-leaning and ‘quality press’ as well.

In conjunction with Leonie Ansems de Vries at King’s College London, I examined the racialisation of EU migrants in British print media prior to the referendum as part of my dissertation research, examining 125 articles published in The Sun, Daily Mail, The Guardian, and The Times between 23 May and 23 June 2016.

I found that through frequent discussions of numbers as well as evocations of threats to national security, these outlets – both left and right – contributed to the effective racialisation of migrants as a distinct group. In this article, I highlight some of strategies as well as the words, metaphors and adjectives used in relation to immigration that made this possible.

Playing the numbers game

Statistics were used by The Times, The Sun and Daily Mail in ways likely to provoke fear by amplifying the scale of immigration. The Sun (14 June), for example, claimed that there are “100 migrants an hour getting European passports”, inciting shock and perhaps even anxiety that Britain will be overwhelmed by a large amount of immigrants. More sober statements of statistical ‘fact’, when removed from context or framed in particular ways, had potentially similar effects.

The Times (27 May), for example, reported that “Romanian and Bulgarians accounted for 58,000 of the net figure [of 333,000, total net migration to Britain in 2015], up from 44,000 in the previous year”. Singling out Romanian and Bulgarian arrivals – the former an especially frequent target of racist tropes – and emphasising the arrival rate without contextualising information serves to reduce those coming to Britain to indistinguishable, countable ‘units’ that are increasing in volume over time without a known cause.

This helps to present a situation that can feel self-propelling while feeding long-standing strains of racial prejudice in society, and does nothing to humanise the experience of individuals moving for equally individualised reasons.

Numbers also become more startling when used in conjunction with metaphors and imagery that connote threats or violence.

The Sun (31 May), for example, referred to the “invasion of the UK”, suggesting that Britain is under attack and associating migrants with violent enemies. Elsewhere on the same day, The Sun likened migrants to natural disasters, arguing that Britain faced a “flood of 500k” immigrants. Hyperbolic metaphors of ‘waves’ and ‘floods’ signal extreme movement and a lack of control, adding weight and urgency to the Leave campaign’s message of “take back control”.

The Sun attempted several times to ward off criticism that their immigration narrative was racialised, arguing that “(their) objection is not about race. It is about the weight of numbers and Britain’s inability to cope with them” (17 June) and that “it is not racist/xenophobic to worry about mass immigration” (6 June). However, the arguments the tabloid put forward were not about Britain’s inability to cope with immigrants. Instead, they were about excluding immigrants on the basis that they are different and inferior, using numbers to overshadow any other perspectives.

For example, The Sun (28 May) argued that remaining in the EU leaves Britain open to the risk that Turkey might join the EU and cited the population of Turkey as “80 million”, leaving open the suggestion that this is also the number of potential Turkish migrants to Britain and as such should be seen as a threat. Turkey’s Muslim majority also finds frequent reference, for example Daily Mail (14 June) claimed that “100,000 Turks would flock to Britain every year if the Muslim country become an EU member”.

The positioning of Turkey as being a “Muslim country” serves to establish its cultural and religious difference, and baseless or unrelated yet invariably large numbers serve to overwhelm and create a sense of danger. Tabloids have a long and established narrative regarding the suspicious Muslim ‘Other’, and are able to call upon it without indulging in explicit Islamophobic rhetoric. Positioning Britain as at risk of a possible influx of Muslims is all that is needed to play into already entrenched narratives about the religion and its followers.

The Sun’s denial of racism, while continuing to argue along racist lines, is a central discursive technique in racialisation and was employed liberally in the lead up to the referendum. Despite denials of prejudice clothed in appeals to basic maths, the rhetoric centred around ‘keeping them out’ – not around improving Britain’s capability and efficiency of public services or demanding that politicians create more inclusive policies. Immigrants are thus racialised by being presented as a risk due to their potential numbers, a deliberate tactic of scapegoating that reinforces unequal power relations.

Clogging up the prisons

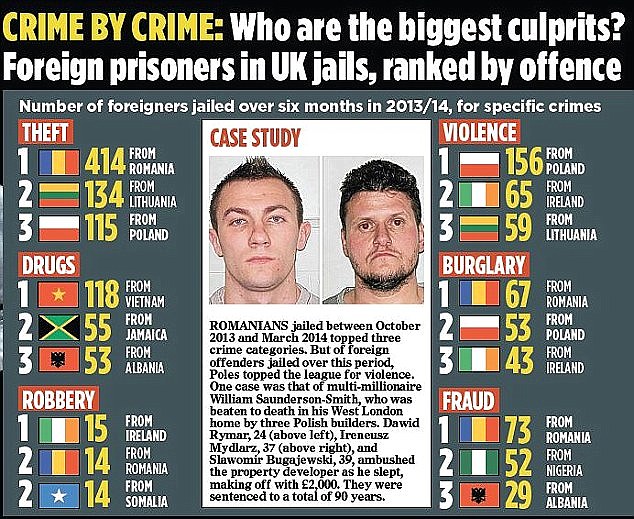

Newspapers also racialised immigrants by attributing criminal tendencies to them and by presenting these criminal traits as fixed and constant amongst all immigrants. Immigrants were thus degraded and portrayed as less deserving of inclusion. The Daily Mail’s (3 June) description of “1,000 Polish and 600 Romanian criminals” as “violent thugs and rapists … clogging up our prisons” exemplifies this.

The verb “clogging up” suggests excessive overcrowding, and it is linked to notions of waste and dirt, dehumanising immigrants as being worthless and inferior. By associating such descriptions to immigrants in prisons, they are not only cast as impediments to the smooth functioning of society’s institutions but also as deviant and despicable.

The verb “clogging up” suggests excessive overcrowding, and it is linked to notions of waste and dirt, dehumanising immigrants as being worthless and inferior. By associating such descriptions to immigrants in prisons, they are not only cast as impediments to the smooth functioning of society’s institutions but also as deviant and despicable.

The Times (June 20) also described Romania “with its East European criminal gangs” as “one of the most corrupt countries in the EU”, adding that “Romanians were the third-largest group of foreign prisoners to be jailed in Britain in 2014. They also account for almost half of all foreigners recorded by British police as having been convicted of a sexual offence abroad”. This suggests Romanians have criminal characteristics because of who they are and where they come from, and thereby racialises Romanians as inferior and undesirable.

The trope of the criminal migrant often intersected with the trope of the migrant benefit scrounger. For example, the Daily Mail (2 June) featured a story about a “one-legged Albanian drug dealing double-murderer” who obtained “citizenship … a lovely house and £500 a week of benefits”. Throughout this and similar stories the British criminal and the foreign non-criminal are conveniently forgotten, so that crime becomes something inherent to foreigners, something done by the ‘other’ rather than the ‘self’.

Another Daily Mail article (9 June) describes the same Albanian criminal as having “gouged out the eyes of one victim”, and stresses that Albania is “a country which wants to join the EU”. The link made here is explicitly racist: the article positions the Albanian criminal as representative of the wider population of Albania, and uses him as a justification for why opening the door to Albanians is the same as opening the door to criminals.

A matter of national security

Immigration was portrayed as a threat to the security of various issues and immigrants were exhibited as a dangerous and unwanted burden, while Britain was rendered as the victim of injustice and pressure. The Sun (May 31), for example, argued that schools, roads and hospitals, “already creaking under the strain on EU free movement regulations”, would struggle to deal with more immigrants. This idea, that immigration “wrecks Brits’ chances of homes, jobs and schools” (The Sun, June 10), or that “immigration (is) heaping extra pressure on housing, public services, the NHS” (The Sun, May 28), was repeated in the month preceding the referendum.

By problematising immigrants as endangering Britain’s quality of life and framing them as a drain on already limited public services, a sense of resentment is created towards immigrants. These are examples of securitisation, a strategy that represents a factor as a threat to the security of others.

In this case, immigrants were framed as damaging to the economic security, social stability and national identity of Britain, resulting in a racist discourse and exclusionary effects.

Moreover, blame is assigned to immigrants for many of Britain’s structural problems – they are the ones that are causing difficulties, lengthening waiting times and causing the housing crisis. A Daily Mail (May 28) article titled “migrants have cost my disabled mother new home”, imparts that “a woman … and her disabled mother had missed out on a council home six times because of EU migration”.

This scapegoating of immigrants for society’s problems, rather than placing the emphasis on larger problems of supply, has been rebuked time and time again by scholars to little effect. Indeed, while the Daily Mail (June 13) did quote Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn as saying the “politicians who won’t build enough houses (are) to blame, not migrants”, they headlined the article as Corbyn “in denial”, effectively dismissing his position in its entirety.

Worthy of representation

The tabloids, as well as The Times (despite being pro-Remain), engaged in blatant scaremongering by portraying East European immigrants as a symbolic bullet that Britain could dodge by leaving the EU. The Guardian, on the other hand, addressed myths about immigration and offered counterclaims to arguments that immigrants had an adverse impact upon the economy.

Immigration was approached from a positive angle and articles tried not to portray immigrants as a problem – at least one that would not be solved by Brexit. The Guardian was the only newspaper that introduced the voices of immigrants themselves into the referendum debate – the other newspapers spoke about immigrants, but did not speak to them.

One article from The Guardian (June 3) included the stories of five immigrants from the EU, one of whom also voiced his concern that the referendum “could legitimise xenophobia”. In the same story a German-national social worker expressed her feeling that she made “a real difference to the community”, and noted that immigrant “GPs, social workers, entrepreneurs, midwives, dentists, nurses, teachers” carry out “vital jobs” in the UK. This counters descriptions of immigrants as ‘scrounging off’ Britain – images that were so prominent within the discourses of other newspapers.

Despite this, such framings also served to homogenise immigrants on the opposite side of the spectrum, evident when we consider who was quoted and who was not given a voice. Most of those quoted were from West Europe, not East Europe, and they all held rather affluent, high paid jobs, reflecting a superior class and status. Both East European immigrants and those working in the so-called 3D jobs – dirty, dangerous, and dull – remained invisible and unrepresented. This reflects a subtle form of viewing race as class, where only those who fit the definition of being ‘white’ in the sense of class are allowed representation.

There are thus shades to ‘whiteness’: having a more affluent job instead of being in poverty or having a low income makes one more ‘white’, and therefore more desirable. This reflects a new form of racism that is not colour coded –the scholar Sivanandan (2001) calls it “xeno-racism” – where “poverty is the new ‘black’”.

Exclusionary politics

‘Whiteness’ is thus malleable and depends on context: in the EU Referendum, the Leave campaign sought to exclude Britain from the EU, and the main factor that it put forward to justify this was that immigrants had to be excluded from Britain. Britain had to take back control from racially different and dangerous immigrants. This exposes a more fluid notion of race that changes over time in accordance to social, political and economic context.

In short, the media framed the EU referendum debate as one related directly to immigration. By inciting fear and worry about the uncontrollable immigration of dangerous ‘Others’, newspapers established a narrative that presented Brexit as the only solution to this ‘problem’. Whether tabloids are the cause or the symptom of racist discourses needs to be questioned: Daily Mail and The Sun evidently based the EU debate around race and immigration, but these narratives also circulated in the broader public and political debate.

It is important to consider whether the hostile atmosphere of insecurity, sustained by the media and politicians during the lead-up to the referendum and the outcome of Brexit, will lead to the creation of further populist policies. Resorting to simplistic solutions that are in part based upon racialised accounts of immigration will not solve the complex problems facing Britain. Instead of attributing blame for many of society’s ills to immigrants, there is a great need to rectify this and place the blame and responsibility where it belongs: onto the rhetoric and policies of those in power.

Xenofobia impotriva romanilor devine normala in Marea Britanie

4 Comments

In mod ironic, intoleranta fata de straini e mai mare printre oamenii care iau contact mult mai putin cu ei.

Ce-mi plac astia care spun “mie nu mi s-a intamplat, deci nu se intampla”. Fratilor s-a scris inclusiv in presa britanica despre asta. Sigur daca esti “corporatist” si locuiesti intr-un centru universitar esti oarecum in siguranta, dar nu toata lumea locuieste in zonele bune din Londra.

Multi spun ca daca muncesti nu are nimeni nimic cu tine. Partial corect dar si in Anglia sunt zone si zone. Intr-o regiune mai saraca, unde exista deja somaj, nu se bucura nimeni ca vin niste romani (sau alti est-europeni) care accepta un loc de munca pe un salariu mai mic decat cel cerut de un localnic. In momentul in care alegi sa locuiesti intr-o zona saraca a unui orasel mai mic, sansele sa suferi fel si fel de agresiuni (macar verbale) cresc.

“In August 2016, the Polish Embassy in London has said it was “shocked and deeply concerned” by reports of xenophobic abuse directed against the Polish community following the Brexit vote. Two months later, a Polish man was attacked and killed in a suspected hate crime.”

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/racist-hate-crimes-surge-to-record-high-after-brexit-vote-new-figures-reveal-a7829551.html

Niciun un roman sau mai bine zis est-european, ca in aceeasi oala intra toti care stau la est de Austria, n-ar trebui sa-si deschida gura cind vine vorba de toleranta. Trebuie sa reamintesc de isteriile gen familia traditionala, orletele celor din noua dreapta de ficare 1 decembrie, scandalul din muzeul satului, fata cu micii, medicii care batjocoresc copii ca nu stiu bine romaneste, etc.?

Unii se simt discriminati in vest deoarece in loc sa-si vada de treaba ei umbla cu smecherii sau se cred buricul pamintului. Daca esti modest, nu faci scandal si incerci sa te integrezi esti binevenit oriunde. Insa daca umbli cu obiceiuri de acasa, urli pe starda, asculti manele la maxim, faci gratare si te-mbeti, stai si astepti ca altul sa dea o matura in fata casei, iti bati nevasta si copii, normal ca lumea vede ce fel de om esti si nu mai sta nimeni de vorba cu tine.

Cea mai recenta grozavie romaneasca din Germania: au furat si mincat animalele de la gradina zoologica din Berlin.

urli pe starda, asculti manele la maxim, faci gratare si te-mbeti,iti bati nevasta si copii,asa sunt multi romani in uk